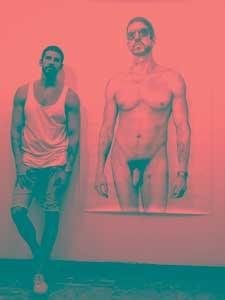

Zachari Logan stands beside one of his self-portraits. Credit: Courtesy of Zachari Logan

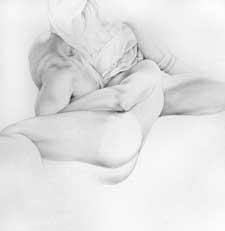

Two men lie together, naked. They are close to each other but not touching. A swath of fabric covers both of their heads, intimate but anonymous.

In another, one man is curled up, ass exposed, head tucked close to another man’s chest and armpit. The second man leans back, so they could be making eye contact, if it weren’t for the fabric joining their faces. In the background, a tube sock is clearly visible, a nod to gay culture.

They are quiet pictures, but, like most of Zachari Logan’s work, there’s violence behind the stillness.

The hoods are sinister — part SM blindfold, part executioner’s mask, part Abu Ghraib torture hood.

The Lazarus Series, which comes to La Petite Mort in February, is the extension of a project Logan began while doing his master’s thesis at the University of Saskatchewan. There, he found himself drawing pictures of suicide bombers in gay embraces.

The Lazarus series uses the same explosive raw material — nudity, violence, religion, gays — but it is one step removed.

“Essentially, they were about queer relational dynamics,” Logan says. “With the earlier drawings, they were actually touching, but in the other drawings, none of them is actually touching. Their body language may be intimate…” His voice trails off.

Logan, a Catholic-raised atheist, shows an attitude toward religion that is somewhere between playful and belligerent. In another series, Logan drew himself as Saint Sebastian, pierced with pencils. In one drawing, titled The World is Flat, there’s a mocking depiction of Noah’s Ark.

Logan has read extensively about Lazarus. His research includes speculation, largely from non-canonical sources, that Jesus and Lazarus were lovers.

“It’s the secret passage of Lazarus. It’s actually very homoerotic. Jesus raises Lazarus from the dead and then he took him, and taught him, and there are all these references to homosexual relations,” says Logan.

Logan, a 29-year-old fine art grad living in, of all places, Saskatoon, is also a flawless technician. Years of life-drawing practice has given him a confident hand and an uncanny ability to reproduce the body in pencil.

In his work, the male body is used sculpturally, even architecturally. The pictures are creepy, but also sexy.

“I have absolutely no problem with objectification. If you’re using an image, you’re always objectifying it in a way,” he says.

If he concentrates on athletic, handsome subjects (most recently, himself), it’s partly because of his interest in neoclassical painters like Jacques-Louis David, Jacob Ungerer, Antoine-Jean Gros and romantic painters like Eugène Delacroix.

At the Louvre in Paris last summer, he says, he spent his time looking at the way men were depicted, especially how they touched each other.

“The male bodies are supposed to be these representations of bravado and heroism, but they’re also very sexually charged, in my opinion. So that’s how I subverted or transformed the technique,” says Logan. “I zeroed in on parts of the drawing where there’s that kind of homosocial, homoerotic horizon, and I drew them.”

And that’s just one of the take-home messages from his time in Paris. Logan, clearly, isn’t afraid to find politics in his work.

“One of the things I noticed, right off the bat, was when you look at those paintings now, they don’t look like they have much of a political message. People tend to admire them for their aesthetic value — which is incredible — and that’s fine. But a lot of the original political messages are lost.”

He wants to provoke his audience, and he says he is never surprised by their reactions — except, perhaps, for the visceral reaction of his mother to the Saint Sebastian portrait.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra